Groupe Mobile : retracing the social life of artworks through photography

From February 13 to July 2, 2016

With Yaacov Agam, Andrea Ancira (Pernod Ricard Fellow), Ellie Armon Azoulay, Kemi Bassene, Yogesh Barve, Kim Beom, Jean Bhownagary, Judy Blum Reddy, Constantin Brancusi, Alexander Calder, Luis Camnitzer, CAMP, Esther Carp, Clark House Initiative, Camille Chenais, Justin Daraniyagala, Jochen Dehn, Cristiana de Marchi, Max Ernst, Mitra Farahani, Joanna Fiduccia, Alberto Giacometti, Alberto Greco, Zarina Hashmi, Iris Haüssler, MF Hussain, Sonia Khurana, J.D. Kirszenbaum, Naresh Kumar, Emmanuelle Lainé, Laura Lamiel, Life After Life, Nalini Malani, V.V. Malvankar, Ernest Mancoba, Julie Martin & Billy Klüver, Henri Matisse, Tyeb Mehta, Adrián Melis, Marta Minujín, Martine Mollo, Juana Muller, Tsuyoshi Ozawa, Prabhakar Pachpute, Akbar Padamsee, Amol K Patil, Rupali Patil, Pablo Picasso, Edward Quinn, Nikhil Raunak, Man Ray, Krishna Reddy, Edward Ruscha, Gerard Sekoto, Suki Seokyeong Kang, Sumesh Sharma, Amrita Sher-Gil, Shunya, Francis Newton Souza, Pisurwo Jitendra Suralkar, Sharmeen Syed, Jiři Trnka, Marc Vaux, Marie Vassilieff, Georges Visconti, Susan Vogel, Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, Caroline Zelnik and many others.

Curators: Mélanie Bouteloup & Virginie Bobin

With the complicity of MNAM CCI – Centre Pompidou

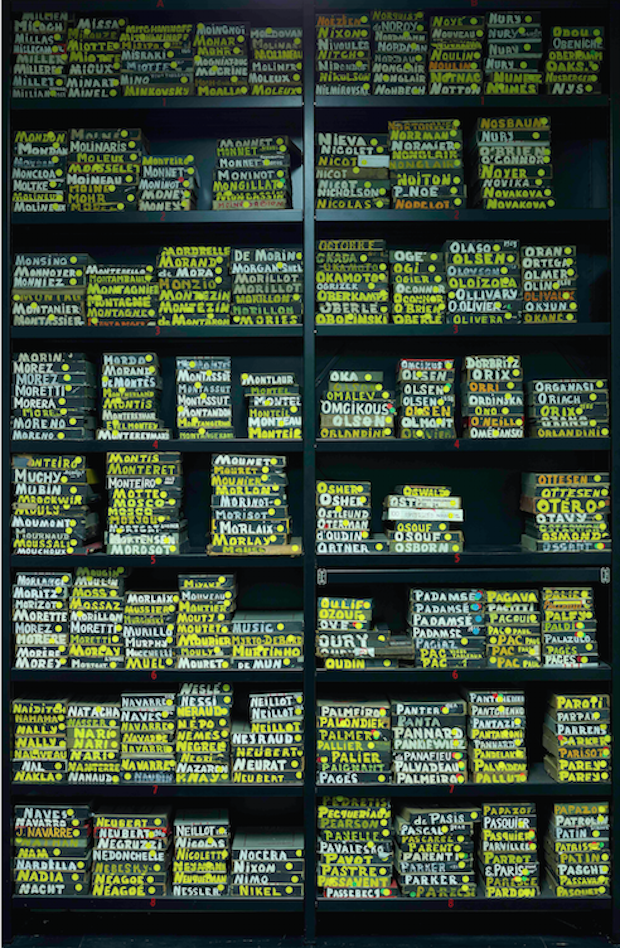

- Bertrand Prévost, Marc Vaux Archive, 2015 (c) Centre Pompidou – Mnam – Bibliothèque Kandinsky.

A former carpenter who took up photography after being injured in the First World War, Marc Vaux began in the 1920s to carry his photographic chamber around the various artist studios of Montparnasse and Paris. By the early 1970s he had produced over 250,000 glass plates. To stand in the reserve holdings of the Centre Pompidou (where the collection has been housed for the past thirty years) and hold in gloved hands a photograph by Marc Vaux is to watch as the margins of history and of the work of artists—which the photographer kept out of frame sometimes with a strip of black tape—come to life. It is to pick up the trail of works of art lost during the Second World War. It is to observe all the objects, images, and newspaper cuttings that together paint the landscape of the artist at work, but also to see the movement of the artist’s works, piled on top of each other on the floor, leaned up against walls not yet prepped as picture rails, rich in lives juxtaposed in hybrid and transitory assemblages, in the manner of what Constantin Brancusi called his groupes mobiles (mobile groups).

Our exploration of the Marc Vaux Archive acts as a point of departure for the Villa Vassilieff’s inaugural project, where we re-examine, in a dialogue with contemporary artists and associate researchers, the photographs, their production contexts and the historical narratives attached to them. Rather than set our sights on the unattainable ideal of an objective and definitive history, we focus instead on the investigative process involved in the creation of these histories: reading, verifying, unframing, comparing, dating, digging, identifying… Today, as the Centre Pompidou is set to undertake the mammoth task of digitizing the archive, we have a unique opportunity to partake in the precise cataloguing of thousands of glass plates, and examine the process of patrimonialization itself as it is being carried out in as many actions, manipulations and reconditionings as there are new photographic images. What do we preserve? Where do we store the glass plates? How do we name and class them? According to what criteria? How do we put them back into circulation given the fragmentary information we have for so many of them? How do we foster productive fusions with other resources themselves isolated in other reserve holdings? Where do we begin?

At a time when it is necessary to challenge the (intellectual, geographic, economic) modes of accessing knowledge, we might imagine collective and intuitive ways of working that go beyond disciplinary borders, beyond the single academic field, to make way for singular interpretations and to reassert the role of art as a “contact zone” for society.

The Villa Vassilieff’s inaugural exhibition, entitled Groupe Mobile, invites the visitor to a double immersion: into the Marc Vaux Archive, and into the renovation process of Villa Vassilieff. We thus chose to initiate a dialogue between many photographs and objects gathered during the year that we spent planning for the Villa Vassilieff. Through the lens of photography, Groupe Mobile intends to draw the contours of an institution willing to set in multiple motions again the history of art as a discipline that is still too anchored (especially in France) in Eurocentrism and the weight of Academia. After a discussion with the director of the Ateliers Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris (our neighbor in Montparnasse), during which he shared his desire to move away from the French academic tradition, we chose to gather at Villa Vassilieff a few of the works found in their studios (by Martine Mollo and Caroline Zelnik), as an invitation for them to play truant.

The scream expressed in Kim Beom’s video underlines — with a certain irony — this will to set free from the weight of a tradition that continues to stand on a largely formal appreciation of the work of art, still perceived as a finished product rather than as the fruit of a process. This is also at stake in Luis Camnitzer’s participation in Groupe Mobile, him who embraced teaching and pedagogy so that they would never be separated from life. Write the biography of an idea thus invites visitors to reflect on the trajectories of ideas and works, and transform their apprehension. This leitmotiv also guided the choice of including Man Ray’s film Étoile de mer. With the complicity of Kiki from Montparnasse, Man Ray disrupts the conventional codes of perception. Filmed through thick glass, the characters are blurred, and the film calls for a constant exercising of our gaze. Groupe Mobile thus encourages companionships that may at first seem unusual or anachronistic, yet that help us rethink our relationship to works and ideas.

Exhibition views, photography of artworks and artists, and the reconstruction from archives permit a wider focus on the artwork to encompass social, economic and even political data. The incredible epic journey of a Fang sculpture—recounted by Susan Vogel in her 8-minute film—offers a brief run through of the transformations undergone by works of art through eras and fashions. We watch the piece, within each environment, evolve according to the various production contexts it is slotted into (or rather lose its personality, as recounted in Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa’s intervention). This is exactly what is at stake here: understanding the complexity of circulations and encounters at play in the formation and the life of works, which Edward Ruscha wished for in his text The Information Man. As a terrain, Montparnasse appears to be a good departing point to study them.

Our first exploration of the Marc Vaux Archive gave us access to the work of artists such as Esther Carp, Pan Yuliang or Francis Newton Souza, who emerge as a few of the portraits of this cosmopolitan Paris. The curators of Clark House Initiative chose to feature the interactions and relations (including amorous ones) between Indian and international artists from the 1960s up to this day, with, as focal points, Paris and the painter, filmmaker, ceramicist, magician, film producer and indefatigable host Jean Bhownagary, who held a position at UNESCO for nearly forty years and whose work now occupies every nook of the apartment where his daughter still lives in Boulogne. The extraordinary work carried out by Clark House Initiative on thinking about the history of art differently, outside of museum institutions, while giving a voice to very young artists, seems to us to be of crucial importance. The constellation of artists and materials they brought together and scattered throughout the exhibition reveals and stimulates new encounters between artists as well as the migration of ideas, through circulations that challenge the concept of national identity in art and a homogenous and Eurocentric notion of modernity.

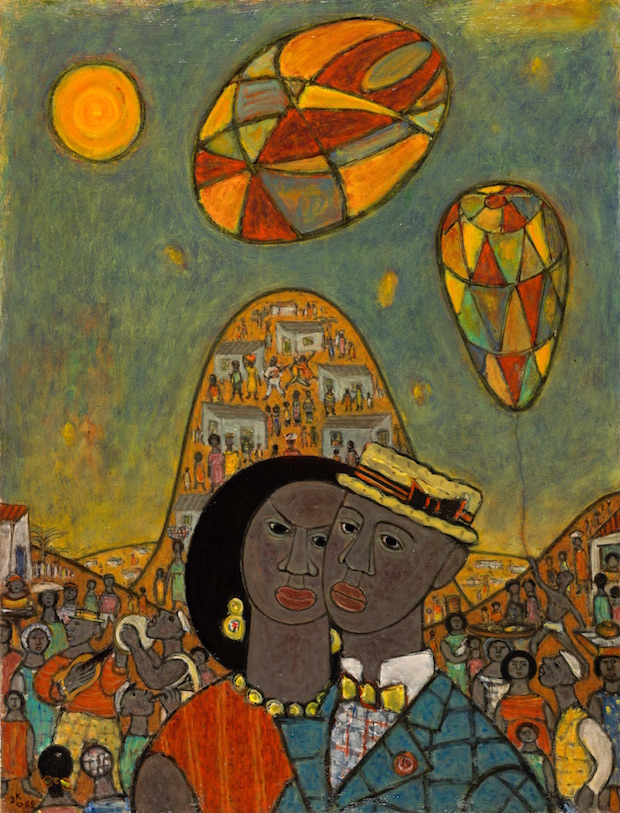

Looking into the Marc Vaux Archive is also tackling (tearing into) the blind spots of art history, the lost works of art, the artists (mostly women) absent from hegemonic or partial narratives (like Marie Vassilieff), which too often relegated them to the roles of friends, muses and hostesses... It is in part thanks to the Marc Vaux Archive that Nathan Diament was able to track down the work of his great uncle J.D. Kirszenbaum, work that was scattered or destroyed as the painter fled the rise of Nazism in Berlin in 1933, and then occupied Paris in 1940. Kirszenbaum was associated with the “School of Paris” (less a movement than a “historical event”)—the convergence, particularly around Montparnasse, of a number of artists and intellectuals from diverse geographic and social horizons. Whether passing through or settling there for the long-term—or taking on French nationality, even—these artists developed the language of polyphonic modernity, resolutely transnational and sustained by individual histories and political engagements too often faded out by the linearity of official narratives.

- J.D. Kirszenbaum, Célébration de la Saint-Jean à São Paulo, 1952, FNAC 29874, Centre national des arts plastiques © all rights reserved / CNAP / photography: Yves Chenot.

There is always some speculation in archive work. Even in photography, gaps remain, and it is not about wanting to fill them all. The task is grueling, the materials often difficult to access, the information contradictory, and memories fallible or hard to share, as witnessed in the film by Adrián Melis, as well as by Mitra Farahani about Bahman Mohassess. Fiction sometimes enters into play as a way of thinking about research methodologies in art history: take Iris Häussler’s mad project on the life of a fictional artist, Sophie La Rosière, or Tsuyochi Ozawa’s attempt to imagine Tsuguharu Fujita’s presence in Indonesia during the Second World War. In short, we wish to provoke official history and chronologies so that we may challenge them and confirm that they are written according to selected points of view one is required to know. To consider their shadows and their bright spots, the play of light, like in the photographs of Brancusi, who in his groupes mobiles incorporated the moving point of view of the spectator into the creative act. The films shot by Brancusi in his studio influenced Sonia Khurana, who, using her own body as sculpture, imposes a different figure—that of a non-European woman, with generous curves and a burlesque manner, who resolutely appropriates both the artist’s work space and traditional representations of art. It’s not anymore a matter of making sculpture move, but of bringing one’s one self into motion, in an act of emancipation.

To search photographs—especially in their margins—for the social life of artworks and the movement that brings them into being, is also to notice with which tools, gestures and readings it is shaped. It is paying attention to what lies around the studio, what is collected (see photograph by Edward Quinn in Pablo Picasso’s studio), what encounters take place there, and perhaps then to step out for a stroll, like Picasso and Jean Cocteau did in Montparnasse one sunny afternoon in July 1916, rediscovered by Billy Klüver and Julie Martin in the early 80s. Photographs taken by Harry Shunk of Marta Minujín’s public destruction of her artworks, contributed to the documenting, circulation and “collection” of performances, reshaping the relationship between works of art and their photographic representation.

There are so many ways of setting artworks back into motion, and Groupe Mobile attempts to choreograph these multiple possibilities. Thanks to the Marc Vaux Archive, works can be observed in unusual contexts, like Max Ernst’s sculptures, photographed on Parisian rooftops. The camera has the ability to capture different facets of an artwork, from the front, the sides, from below… Works by Yaacov Agam and Julio González are photographed from various points of view. The movement of the work itself is sometimes grasped by the camera within a single shot: Alexander Calder’s works have thus been paradoxically immortalized in movement by Marc Vaux.

- Marc Vaux Archive, 2015 (c) Centre Pompidou – Mnam – Bibliothèque Kandinsky.

For Henri Matisse, photography was a tool to record the different stages of his paintings in progress. Marc Vaux photographed series he exhibited to retrace the elaboration process of his artworks. The funds thus offers alternative approaches to works by artists deemed too well-known. Our exhibition also includes series by Jean Bhownagary, who tested different ideas around a same motif on wood or metal plates, generating as many variations or co-presences. This idea of the motif is central to the exhibition. Similar forms reoccur, duplicate and transform following their reproduction on different media (like when Joanna Fiduccia retraces successive apparitions and evolutions of a sculpture by Alberto Giacometti); or when their author himself reproduces them through various forms, like Jean Bhownagary with scarves, ceramics, engravings or watercolors. Repetition never really repeats itself, but expresses the flow of creation, constantly nurtured by various influences.

A drawing by Bahman Mohassess representing one of his most often recurring motif — a fish — is displayed next to artists he was fond of: Calder, Brancusi and Matisse. In the margins, a quote by Andy Warhol, grand master of repetition and proliferation of artworks in the fabric of daily life — “into direct contact with people and things,” as Alberto Greco would say, albeit with very different motivations. It is that kind of relations between artists so often separated in the great narrative of modernity’s history that Groupe Mobile seeks to bring forward. Ernest Mancoba, for instance, is one of these artists whose work transpires from exchanges he would have experienced while traveling around the world.

It was important for us, within the non-linear story that we attempt to unfold in Groupe Mobile, to invite artists to contemplate this space, and to inhabit it, in an alliance that is respectful of its history—not to seek to transform it, but to work with it. Jochen Dehn is restoring it. Karthik Pandian and Paige K. Johnston (Life After Life) are filling it with animated furniture. Laura Lamiel is moving an “instance” of her studio into it and regularly inhabits it. Suki Seokyeong Kang is staging an installation that cuts through and reframes the space. Emmanuelle Lainé is creating a spatio-temporal trompe-l’œil, a mise en abyme of different modes of photographic staging, with the complicity of André Morin. The result of two weeks’ work at the Villa Vassilieff, Une méthode des lieux includes both photographs from the Marc Vaux funds and fragments of the ongoing restauration of the Villa Vassilieff, and for the first time, the bodies that worked on it, suspended in a moment of artificial rest that can recall the artists’ poses as portrayed by Vaux. The installation is inviting us to take an active stance and question assigned categories (sculpture and/or photography, inside and/or out) and the boundaries separating work, relationships and representation.

To sustain a critical doubt: must we look at photography and what it represents, or what is outside of it? It is important to approach works of art by multiplying perspectives, and most importantly to move them back into the center of the public sphere, away from the sidelines or the reserve holdings of institutions. Observing the movement of works and artists, stimulating new ones, using different tactics: to endlessly undertake the task of zooming in, zooming out, assembling and juxtaposing; to pay attention to margins and borders, especially where they warp; to play with different methods of hanging, involve multiple collaborators, where they artists, researchers, neighbors… We thus worked with Camille Chenais and Ellie Armon Azoulay, two researchers who accompanied our exploration into the Marc Vaux Archive. We also invited team members who work on the renovation of Villa Vassilieff to leave traces of their passage through souvenirs of their choice.

Based on these alliances and a few trajectories we crossed during our research, we imagined moving as if on a path through the spaces of the Villa Vassilieff, like a house where one can amble through its rooms, read or chat with a passing guest, while always staying in touch with the outside. The key is for these conversations to spread permanently to programs in institutions, and multiply in various places and in different ways. It is also about building ties with the neighborhood (like with the Ateliers Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris), learning centers, universities and art schools, with a new generation of civic organizations. Nourishing the less exclusive representations and customs of our heritage offers a greater chance for independent, original, and non-reductive initiatives to emerge.

— Mélanie Bouteloup & Virginie Bobin

We would like to thank Bernard Blistène, director of the Museum of Modern Art, Catherine David, adjoint director of the Museum of Modern Art, Didier Schulmann, curator at the Museum of Modern Art and department head of the Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Catherine Tiraby, documentalist of the photographic collections, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, and Nathalie Cissé, loan coordinator, Bibliothèque Kandinsky.

Read more: Culturebox’s article, La Villa Vassilieff : the new artist’s eden at Montparnasse (In French)

Partager